Your basket is currently empty!

Winners and Losers in Changing Climate: How Wildlife is Adapting (or Not)

Meru National Park, known for its unique diversity of northern species and rich predator-prey dynamics, is facing the pressures of climate change and shifting predator populations. With predictions of wetter-than-usual December-March periods but increasingly frequent failures of the crucial long rains in April and May, Meru’s wildlife will see shifts in food, water, and habitat availability. Here’s how some of Meru’s iconic species, from Grevy’s zebras to Eurasian migratory birds, may adapt to these changes—and why others, like cheetahs, are struggling to keep up.

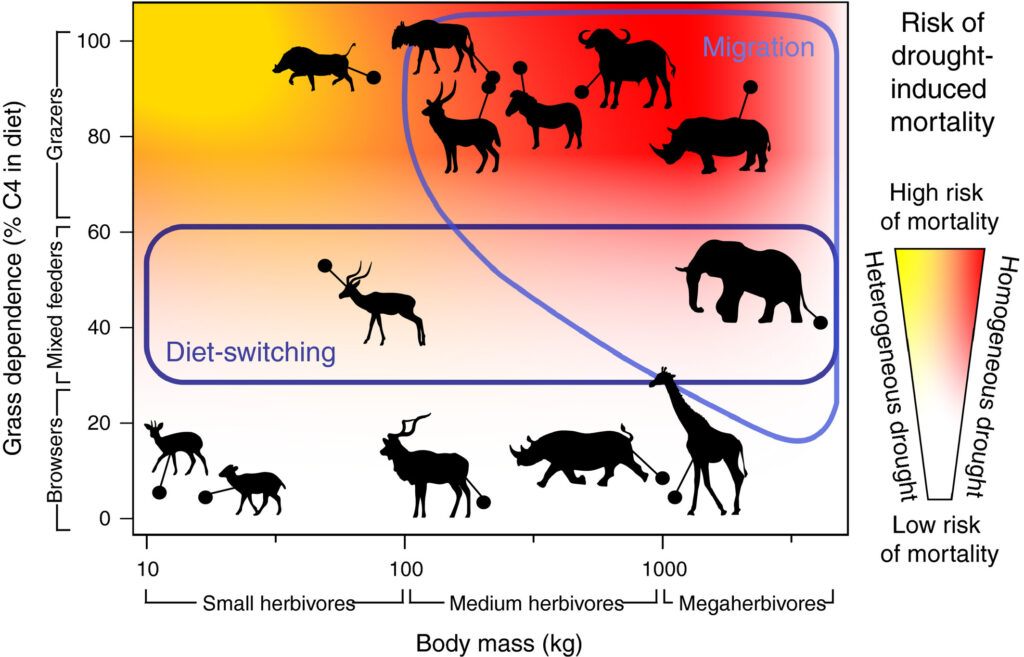

In the face of climate change and desertification, herbivores employ various strategies to survive. Their responses—shaped by diet, size, and mobility—reveal how different species adapt to increasingly scarce resources.

1. Browsers: The Unchanging Strategy Browsers like giraffes and kudus, who rely on trees and shrubs, tend to remain resilient in drought conditions by “not responding.” They capitalize on stable resources, as woody plants are often more drought-resistant. However, while this “no change” approach may provide short-term stability, prolonged drought can reduce the availability of browse. This means that, without the flexibility to adapt or migrate, browsers might be more vulnerable in a climate where prolonged drought is the new norm.

2. Mixed Feeders: The Diet Shifters Species such as impalas and elands can switch between browsing and grazing, depending on the season. These mixed feeders have a natural advantage as they can adjust their diets to match the availability of food, switching from tender grasses to shrubs as conditions demand. This flexibility allows them to survive in diverse habitats. As climate change alters plant communities, mixed feeders could have the most adaptable strategy in Meru, taking advantage of both dwindling grasses and available shrubs.

3. Grazers and Megaherbivores: The Great Migrators Large herbivores like elephants and zebras tend to migrate to drought refugia, areas with more reliable water and forage. With their size, these animals can cover significant distances in search of food and water, accessing resources inaccessible to smaller herbivores. This strategy of moving to more fertile ground makes them resilient against localized drought. Yet, desertification and habitat fragmentation could pose a challenge, as natural barriers and human activities limit their migratory routes.

Which Strategy Is the Most Successful? Ultimately, mixed feeders might have the edge, given their dietary adaptability and smaller home range requirements. However, larger herbivores and migratory grazers could maintain resilience if they retain access to drought refugia and migration corridors. As climate change progresses, mixed feeders and those capable of seasonal migration will likely emerge as the most successful survivors in Meru, able to shift or travel as conditions demand. Here is our guess. What is yours?

Winners: Species Thriving with Wetter Decembers and Flexible Diets

1. Eurasian Migratory Birds

One group set to benefit is Eurasian migratory birds. Arriving in Meru during the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, they can capitalize on the wetter December-March period. Expanded wetlands and richer vegetation will provide ample food, including insects, fish, and other small prey that will flourish in temporary pools. Storks, waders, and raptors, who rely on stopover points with abundant food and water, may find Meru an increasingly attractive wintering ground. This boost in resources could enhance their survival rates and potentially increase population stability.

2. Browsers: Gerenuk and Somali Ostrich

Species like gerenuk and Somali ostrich, both of which can browse leaves and shrubs, are well-suited to drier conditions with unpredictable rain patterns. The gerenuk’s long neck allows it to access high branches that other herbivores can’t reach, while the Somali ostrich feeds on a mix of plants and insects, making it adaptable. The expected rain during the dry December-March period will encourage the growth of woody plants, which may help these species thrive even if grasses become less reliable due to frequent droughts in the long rain season.

Gerenuks are uniquely adapted to arid environments. They must get all water from the leaves they eat as no photos exist of them drinking water! Their elongated necks, small face and ability to stand on their hind legs allow them to reach high foliage, giving them a significant survival advantage in dry landscapes.

3. Mixed Feeders: Impalas and Elephants

Impalas and elephants, which can switch between grazing and browsing, are naturally adaptable and could benefit in Meru’s changing climate. These mixed feeders can respond to variable vegetation availability, switching from grasses to shrubs as conditions demand. This flexibility will help them maintain stable populations as the timing of the rains becomes less predictable.

Losers: Grazers and Predators Facing Resource Shortages and Competition

1. Grevy’s Zebra

The Grevy’s zebra, already adapted to arid conditions, is especially vulnerable due to its dependency on high-quality grasses, which may become increasingly scarce if the long rains fail regularly. Male Grevy’s zebras are territorial, a behavior that hinders their survival in lion-populated areas where movement is crucial for predator evasion. This territoriality has previously led to a lack of males in Meru, resulting in low reproduction rates. If grazing resources become scarcer, Grevy’s zebra populations could face even more challenges to survival and reproductive success. Only a handful still exist.

2. Beisa and Fringe-Eared Oryx

Both Beisa and fringe-eared oryx are desert-adapted, and while Beisa oryx is still present in Meru, the fringe-eared oryx has not been seen in Kora for years and was removed from the checklist. These species rely on sparse vegetation and can survive with limited water, but increased competition and patchy resources could put pressure on the remaining oryx populations. If drought intensifies, it may also further limit the oryx’s already scarce habitat.

3. Cheetahs

Among Meru’s most vulnerable species, cheetahs are at high risk due to the growing populations of lions and hyenas. Unlike other predators, cheetahs are built for speed over strength and cannot defend themselves against more aggressive competitors. Increased lion and hyena numbers are crowding the cheetahs out, with only a handful remaining in the park. This loss of cheetahs may disrupt Meru’s ecosystem dynamics as predator pressures shift in favor of larger, more powerful carnivores.

4. Grazers: Zebras and Wildebeests

With the long rains in April-May failing more frequently, grass-dependent grazers like common zebras and wildebeests will face substantial challenges. These species rely on consistent grass regrowth, which could become less dependable as droughts during peak growing seasons intensify. While some grazers may adapt by migrating to find better pastures, habitat fragmentation and competition may make this strategy unsustainable in the long term. Wildebeests have been seen in Kora, not Meru, recently.

Conservation Implications: Supporting the Winners and Protecting the Vulnerable

For conservationists, maintaining a resilient Meru ecosystem in the face of climate change means supporting both winners and losers. Ensuring access to drought refugia—areas with reliable water sources—will be critical for water-dependent species and grazers. Connectivity between habitats can support species like Grevy’s zebra and wildebeests, enabling them to travel in search of resources. Additionally, promoting drought-tolerant plant species that provide food for both grazers and browsers could help create a more stable ecosystem that can withstand shifting rainfall patterns.

As Meru’s landscape changes, the park’s wildlife will need to adapt or risk being left behind. While Eurasian migratory birds, flexible feeders, and browsers may have an advantage, grazers, cheetahs, and other water-reliant species face a difficult road ahead. By implementing proactive conservation strategies that support habitat resilience and connectivity, Meru can continue to provide a home for diverse species, even in a changing climate.

Additional Risk: Fenced Rhinos Facing Water Scarcity

One major concern is the Rhino Sanctuary, home to over 100 rhinos, which relies on a single river for water during droughts. With the area fenced, these rhinos have no ability to migrate in search of other water sources, leaving them at high risk if the river runs dry. This situation highlights the potential dangers of fencing, which, while protective against poaching, can restrict crucial movement during extreme climate events. The combination of limited mobility and prolonged drought could lead to catastrophic mortality for the sanctuary’s rhino population if additional water sources or drought mitigation strategies aren’t put in place.

Leave a Reply